No audio available for this content.

NOTE: This article is adapted from an April 2025 U.S. National Grid Institute (USNGI) filing with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in response to an FCC Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on wireless location accuracy. The USNGI is a non-profit organization providing educational outreach and technical assistance to federal, state, local, and tribal governments, as well as commercial entities, to facilitate use of the USNG for a variety of purposes and, importantly, to support emergency responders in time critical situations (see usngi.org for more information). — Jules McNeff, GPS World Editorial Advisory Board

The term “golden hour” in medicine refers to the concept that rapid response is essential to improve chances of survival following a traumatic incident. Although the actual “golden” duration may vary, it encompasses the time required for incident detection and location, notification to the emergency call center, dispatch of responders, immediate triage and transport to an emergency medical facility. This timeline assumes that the incident location is clearly identified and effectively communicated to the call center and then to responders. Both the call center and the responders must also be educated in the use of geoaddresses. That is not always the case, and we are all familiar with situations where the location of responders was unclear or responders were misdirected, and victims died as a result.

Since its inception, GPS has been described as providing a “common-grid coordinate system” for users. While well-meaning, this is incorrect, as it does not account for real “coordinate system” differences. In fact, GPS employs a common reference frame, which defines the shape of the Earth based on the latest realization of WGS-84 within the International Terrestrial Reference Frame. People may then superimpose different coordinate systems over the global reference frame for the purposes of positioning, navigation, surveying, geodesy and other applications. These diverse coordinate systems are the “languages of location” that can result in confusion and operational friction if their uses are not deconflicted upfront; the consequences of which can prove fatal in emergency response situations, as emphasized here.

A Universal Language of Location

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has been working for years to address these deficiencies through improvements to E-911 services, both for wireline and wireless networks. Most recently, in March 2025, the FCC issued its (sixth) Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) addressing wireless E911 location accuracy. In it, the FCC focused on requirements for more precisely determining three-dimensional locations, particularly the vertical component in structures. What is missing in this NPRM (and previous versions) is a clear understanding of the means to first identify the horizontal component of the incident location and report it to responders in unambiguous terms.

That missing element is a definition of which “language of location” (reporting format) should be used to identify incident locations to responders. With access to current technologies such as GPS and complementary positioning sources, it is natural to focus on the precision of location technologies. However, it is equally important to address specifically how a defined location is then reported to the responders who must locate it once they are dispatched. Modern technology can deliver precise three-dimensional locations, but the emphasis for responders must first be on understanding the horizontal component. If they do not arrive at the right horizontal geoaddress due to location reporting confusion, then the vertical component, even if it is relevant, does not matter.

The most common reporting format in urban and suburban areas is, of course, the street address. However, even within developed metropolitan areas, street addresses are not always consistent or definitive. In disaster situations, they may not even be present due to wind, flooding, fire or other physical destruction. They are also not useful in rural and remote areas away from established infrastructure. Another common format is latitude and longitude (lat/lon), which the public is aware of but not familiar with in terms of describing a specific location. Additionally, the use of lat/lon is complicated by the fact that it is a spherical system, and a location may be identified in any one of three different lat/lon versions, depending on how degrees, minutes and seconds are combined. Using the wrong version can lead responders far astray, resulting in lives lost. Other formats are available, but many are proprietary, difficult to understand, unfamiliar to the public and/or, most importantly, not directly available from proven position determination technologies such as GPS.

USNGI Presents a Solution

In its filing, the USNGI advocates that the FCC direct wireless communications providers to replace all references to civic (street) addresses and to latitude and longitude in reporting the horizontal component of incident locations with the term “U.S. National Grid (USNG) geoaddress.” It also recommends that the FCC consider rules under consideration that direct wireless providers to display USNG coordinates for horizontal addressing, using z-axis elevations provided by other technologies.

The USNG is a publicly available Federal Standard (FGDC-STD-011-2001) established in 2001 by the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) as a nationally consistent grid reference system and the preferred grid for National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) applications. The USNG creates horizontal geoaddresses that are unique, much easier to understand than latitude and longitude and always identifiable because they are referenced to a global grid and not to local features. In a simple format, the size of a telephone number, the USNG can define locations today to an accuracy of 10 m, far exceeding the 50 m requirement in the proposed rulemaking.

As noted above, USNG geoaddresses provide a clear and unambiguous way to describe locations in areas away from established road networks, or those affected by a natural disaster, where road signs have been destroyed. To make their use by the general public and emergency responders even easier, a variety of free smartphone applications are available today that provide continuous USNG geo-locations when activated.

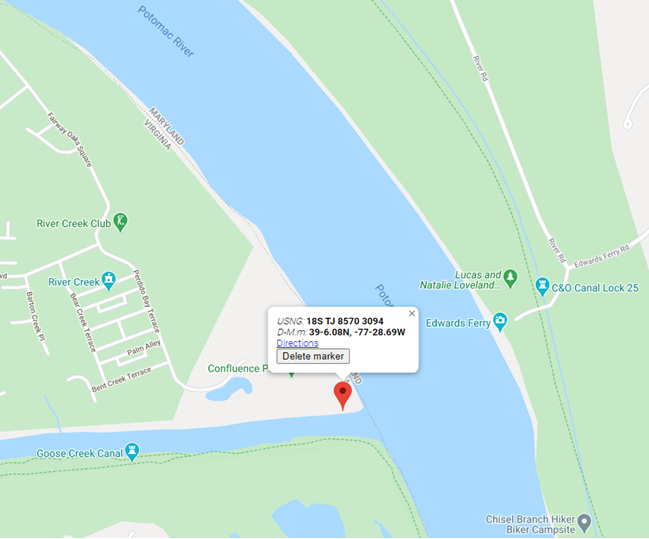

An object lesson is provided by one example (of many throughout the country), the drowning of a teenager named Fitz Thomas on the Virginia side of the Potomac River on June 4, 2020. This tragedy drew much local and even national attention. The teen was swimming at a small creek with friends in a park adjacent to a development, but without a street address. When he got in trouble, his friends tried to help and then called 911 on their cell phones, but could not describe their specific location. Because of the location confusion, coupled with jurisdictional failures, Fitz Thomas could not be saved. If the frightened teens had only been aware of, or had been asked/told by the 911 call center to give the center their geoaddress (which they could have gotten on their cell phones), all uncertainty about the incident location would have vanished immediately, and response could have been dispatched in the instant. The graphic shows the area with a 10 m USNG geoaddress, but which the group was not aware of at the time. The short geoaddress they needed was: TJ 8570 3094.

Real-World Applications

USNG geoaddressing has been adopted by many federal agencies and by several state and local governments to facilitate emergency response operations:

- The Federal Radionavigation Plan (FRP): The FRP, signed by the Secretaries of Defense, Transportation, and Homeland Security, states in Section 1.7.8 (Interoperable U.S. National Grid for Emergency Response Operations) that “…public availability of location-based applications in mobile electronic devices has highlighted the need to create awareness in the USG and among the public of a standard means to identify accident and other incident locations for emergency response purposes. Lack of a uniform method for describing incident locations has been a major impediment to rapid and effective emergency response in diverse metropolitan and rural areas.” It identifies the objective of the USNG standard “…to increase interoperability of location-based services by establishing a nationally consistent and preferred grid reference system to enable user friendly position referencing on gridded paper and digital maps in combination with GPS receivers and Internet map portals.”

- The National Search and Rescue (SAR) Committee (NSARC): The NSARC designated the USNG as a preferred land search & rescue coordinate system in 2011. NSARC manuals specify use of the USNG as the primary georeferencing system for land SAR operations and for air-land SAR coordination. This aligns with coordination of military/civil responder operations as noted below.

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA): In October 2015, FEMA issued FEMA Directive 092-5, titled “Use of the United States National Grid (USNG),” which states as FEMA policy that, “FEMA will use the United States National Grid (USNG) as its standard geographic reference system for land-based operations and will encourage use of the USNG among whole community partners. FEMA will reference and employ the USNG in doctrine, relevant preparedness and grant programs, deliberate and crisis-action planning, training, exercises, operations, logistics, and other appropriate disciplines.”

- Urban Search and Rescue (USAR): FEMA USAR teams adopted the USNG as a response to lessons learned during Hurricane Katrina and subsequently have deployed using the USNG in various disaster response operations. Also, during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and others, Delta State University in Mississippi produced a wide variety of map products incorporating the USNG to assist federal and state emergency responders.

In his statement relative to the proposed rulemaking, Chairman Carr noted a visit to Fire Station 40 in Fairfax County, Virginia. That is the home station for Virginia’s FEMA USAR Task Force 1, a world-renowned rescue team and early adopter of the USNG. The firefighters he met with that day may well have mentioned their use of the USNG in describing to him how location technology assists in the execution of their missions.

- The DHS National Incident Management System (NIMS): The DHS NIMS identifies the USNG as “… a point and area location reference system that FEMA and other incident management organizations use as an alternative to latitude/longitude. The National Grid is simple to apply to support risk assessment, planning, response, and recovery operations. Individuals, public agencies, voluntary organizations, and commercial enterprises can use the National Grid within and across diverse geographic areas and disciplines. The use of the National Grid promotes consistent situational awareness across all levels of government, disciplines, threats, and hazards, regardless of an individual or program’s role.”

- Joint Military/Civil Emergency Response Operations: As noted in the FRP, “The USNG is the civilian version of the Military Grid Reference System (MGRS) that the military uses for tactical operations. It enables geolocating incident locations from 100m to 1m precision.” A Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI 3900.01E) on georeferencing states that, “To support homeland security and homeland defense, the USNG standard is operationally equivalent to MGRS.” As with the MGRS, the USNG is easy to learn by all levels of personnel, it is interoperable if used by civil and military first responders, it improves military support to civil authorities, and very importantly, it reduces operational friction and facilitates crisis and disaster response at all levels from federal to local government.

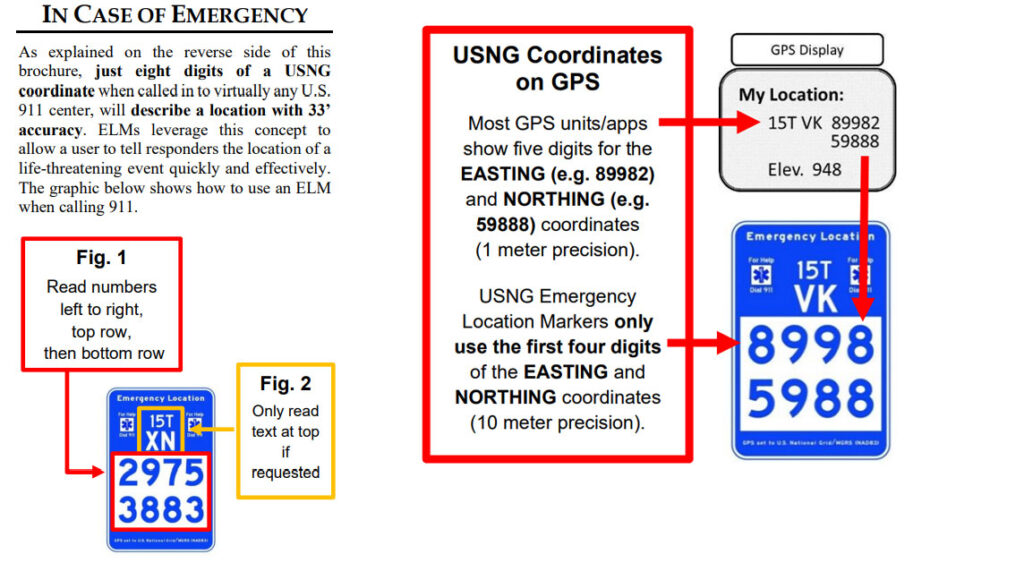

- Emergency Location Markers (ELM): Localities in Minnesota, Georgia, Florida and other communities across the U.S., including National Parks, and even the Kennedy Space Center, have installed USNG-based ELM to give trail and park users a way to report an emergency location. Due to the disparate physical locations involved, nearly all such incident reporting can be expected to come from wireless systems, but to be enabled by reception of GPS positioning signals. The graphics below show the ELM relationship to GPS and how the reporting is facilitated by use of the USNG.