No audio available for this content.

On Sept. 1, 1983, Korean Air Lines flight KAL007, with 269 people on board, went 360 miles off course and strayed into prohibited airspace over one of the Soviet Union’s most sensitive military installations. The pilots, who had missed some radio calls and warning shots, were unaware. Then an air-to-air missile hit the plane.

This tragic Cold War episode helped GPS technology spread from military to civilian use because President Ronald Reagan’s deputy press secretary, Larry Speakes, said that to help prevent a repeat of the tragedy, “the President has determined that the United States is prepared to make available to civilian aircraft the facilities of its Global Positioning System when it becomes operational in 1988.” Civilian use of GPS had been envisioned from the program’s beginning, but Reagan’s announcement now guaranteed the future availability of GPS to civilians. That, and later smartphones, spawned the development of the commercial and consumer GPS industry.

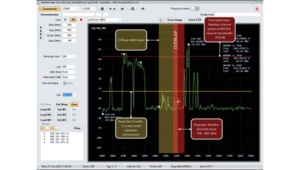

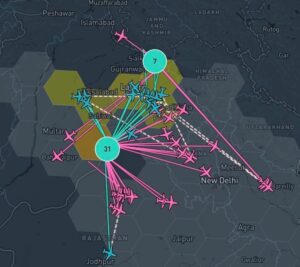

More than 40 years later, however, civilian airliners are increasingly at risk of being shot down, as well as many other equally disastrous outcomes, due to spoofing and its percolating effects on many aircraft systems. GPS Spoofing: Final Report of the GPS Spoofing Workgroup, released on Sept. 6, reports a 500% increase in spoofing this year compared to last year, with an average now of 1,500 flights spoofed per day. Among the many dangers this poses, the report states that it has led to “aircraft entering other Flight Information Regions without clearance or authorization, which creates risk of misidentification and, in the extreme case, interception or shootdown.”

The report, based in part on a questionnaire returned by nearly 2,000 pilots — 56% of them working for airlines and 72% captains — found that more than 90% of all crew members rated their concern as moderate or higher. The three most insidious aspects of spoofing for aircraft are that pilots may not be aware of it; that GNSS receivers may continue to yield incorrect positions long after the aircraft leaves the spoofing area; and that bad data from the GNSS receiver has “severe and cascading effects” on many other systems, including the flight management system, the Ground Proximity Warning System, Hybrid IRS, the aircraft clock, weather radar, CPDLC, ADS-B and ADS-C. Spoofing also affects air traffic control, which is inundated with requests for radar vectoring during and after spoofing.

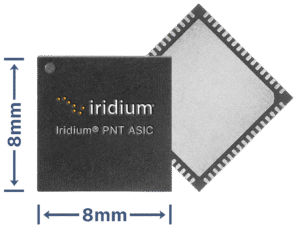

The report finds “an overall sense of complacency and muted interest across a broad section of the aviation industry.” Two of its many recommendations to mitigate the problem jumped out at me: synching a mechanical watch to a known source at dispatch “in preparation for aircraft clock failure” and positioning a handheld GPS receiver “low down in the cockpit such that it only has a direct line of sight to the highest elevation satellites,” which makes it possible “that it may not get jammed and spoofed as easily as the externally mounted antennas.”

Why has it come to this? What will we do about it? You can read the report here.