The surveyor and the cadastre: Why can’t we be friends?

Our ongoing battle with COVID-19 has shown we can adapt to radical changes. A big, but worthwhile, change would be to convert our existing land databases to a cadastre system.

Any place that one may travel around the globe, they will find boundary lines that define properties and regions. For some countries, these parcels may be primarily owned by the government while in more developed nations, a large percent of the land is owned by private citizens.

These parcels, when looked at together, together create a large jigsaw puzzle that seemingly fits together perfectly. Visually, all the lines should fit snugly to their adjacent neighbor so that the sum of the parts equals the whole. This system, called a cadastre, has many redeeming qualities and makes for an efficient choice of keeping an inventory of a region or country’s parcels and infrastructure.

Origins of the cadastre system

The cadastre system of parcel registration is the database of choice for determining land ownership and taxes on property through much of the developed world. Most of the places where this system of parcel registry consists of centralized governments usually have more oversight and legislative power than more “free” countries like the United States.

Also, these countries in which these systems exist are typically small and/or have a manageable number of parcels so the development of the cadastre is much more controlled and maintained.

To help us understand the origin of this parcel system, let us explore the background of cadastre and its beginnings:

cadastre (English version: cadaster) (noun)

Definition: an official register of the quantity, value, and ownership of real estate used in apportioning taxes

Origin: Mid-19th century from French, from cadastre ‘register of property’, from Provençal cadastro, from Italian catastro (earlier catastico), from late Greek katastikhon ‘list, register’, from kata stikhon ‘line by line’.

(Source: Merriam-Webster.com)

In the years after the fall of the Roman Empire and through the end of many feudal societies, land ownership was transferred to individuals and families with the expectation of paying a tax to the government for this opportunity. Landowners could plant and harvest their own crops, raise farm animals for labor, and provide various goods and services to the community.

Besides a small fee for conveyance, the government would ask for a “meager” tax to be paid regularly. Land that was sold to these individuals was recorded in a “cadastre” for tracking of ownership and tax payment. These records were primitive in nature and relied heavily on associating a parcel number to the owner versus an actual legal description to describe the property.

It was not until more sophisticated and elaborate surveying instruments were developed that physical descriptions of the land were used to determine boundaries.

Cadastre system gives way to legal descriptions

This cadastre system of parcel management continues to exist in modern times in many parts of the world with one notable exception: The United States. Some will equate our parcel indexing system as being a traditional cadastre, but this numbering procedure is secondary to the means and methods of parcel conveyance in the U.S.

For the non-surveyor reader, in the U.S. over the past few centuries a multitude of land systems have been used to establish parcel boundaries , each with their own unique system of describing land and conveyances. These types of land transactions began after the establishment of the colonial states and rapid expansion into previously unmapped territories.

The push westward across the country introduced the Public Land Survey System (originated by Thomas Jefferson) and established sectional land divisions. As we encountered (and acquired) new territories, including the Louisiana Purchase and Texas, existing land measuring units and description methods were maintained to preserve these systems. No matter how the parcels are described, we rely heavily on the grantor/grantee system of transfer of ownership and rights throughout most of the country, with parcel numbering being applied post-transaction.

So why is the grantor/grantee system the weak link in the chain of parcel establishment and conveyance? Many times, it comes down to the legal description and how it was created. Our system allows for the creation of a parcel by varying means by the professional land surveyor. The biggest issues occur when parcels are defined by a metes and bounds description with little to no reference to adjoining property or known monuments.

When the legal descriptions of these parcels come into play, that is when the trouble starts, with calls made to attorneys and surveyors to help straighten everything out. To the common layperson who owns land or is looking to buy a parcel, it may seem unthinkable that parcels do not naturally fit seamlessly together with no gaps or overlaps. While the quality of survey data has increased in precision, the accuracy of marrying old data with the new suffers in many ways. How did we get to this point? Let us step back in the not-so-distant past to review how things have progressed throughout my short career.

Set the flux capacitor to the early 1980s…

Before computers and CAD, most agencies adopted a system of parcel and right-of-way mapping manually drafted on large sheets of durable paper or film. Depending on the municipality or county one was in, each sheet could represent either a quarter section (approximately 160 acres) or one half of a quarter section (approximately 80 acres) within a standard section of the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) established by the General Land Office (GLO) of the U.S. (now known as the Bureau of Land Management).

These maps were based upon standard measurements within the given quarter section and drawn using 90-degree corners at the edges of the sheet. The linework depicting the parcels within blocks and larger areas was drawn as close to scale as possible but was intended to be a graphic representation of the shape rather than an accurate reproduction. Considering the technology and measuring devices/capabilities of the time, these records were very helpful in performing retracement surveys of existing properties.

Because these surveys and parcel recordkeeping were performed long before computers, plotters, and CAD software became the norm, surveyors calculated and documented their work using manual computation and drafting from handwritten notes collected in the field. Not every parcel has 90-degree corners and lengths that are integers, so mapping departments for governmental agencies drafted new surveys and parcel boundaries to fit within the existing base sheets. Throw in the varying measurements from different surveyors and we have the real-life jigsaw puzzle that does not fit.

Because the aforesaid mapping departments produced parcel numbering after the creation and conveyance of the property, the damage is already done in conforming with adjacent properties. This is an important factor in the professional surveyor’s responsibility to protect the public when performing an original survey for a new parcel and/or subdivision and utmost care must be observed.

We have an army of land surveyors across the country shaping parcels to fit within a large jigsaw puzzle with an instruction sheet that must be strictly followed. One missed measurement or corner monument is in the wrong position, and we now have two or more parcels that will not fit together in the puzzle.

Many mapping professionals will point, however, to the geographical information system (GIS) and how it improved this convoluted method of parcel databases. But did it?

The digital spaghetti bowl

For a large part of the U.S. where a data-intensive GIS has been created and maintained, it is a step in the right direction, but it still lacks the overall efficiency of a cadastre. Very few GIS databases contain survey-grade parcel establishment on recognized horizontal and vertical datums. Most are parcels and roadways digitized from old mapping and records that are vague graphical representations at best.

One of the most important pieces of the GIS database are the base layers that contain control points and parcel/right-of-way lines that coincide with the datums that govern the region or state. Many governmental agencies do not employ a professional surveyor or surveying staff educated and trained to establish these datums within the database.

Most times, the base layers are established “close enough” using aerial mapping and other data, including handheld GNSS receivers to collect infrastructure improvements. This is not a knock on these departments or individuals; they created the best possible database with the information on hand.

When merged with aerial mapping and/or survey-grade data, the graphical information from the archival records can be confusing and misleading, especially to those who are not educated to understand the data.

Is the cadastre an upgrade?

The reason to consider converting all the existing parcel mapping and subsequent infrastructure/improvement mapping to a cadastre are simple: technology. We have previously discussed cities building digital twins (“Surveying and Geospatial Data,” GPS World, July 2020) utilizing remote sensing and a multitude of GNSS-capable products.

Besides surveyors, many professions and trades use GNSS technology as a tool within their work environments. Our nation has experienced rapid growth in the last 150 years. The Industrial Revolution and the advancement of machinery, materials and building techniques have greatly impacted the ability to build more infrastructure and improvements. Many of these improvements and utilities have exceeded their useful life but have no timelines for replacement.

Developing accurate maps of this aging infrastructure will ensure a proper data set from which a replacement design can be made. Couple this ability to work in a geospatial environment with other datasets, including aerial/satellite photography and lidar acquisition, and it gives us a nearly unlimited ability to map our world in appropriate datums with greater accuracy and precision. Governmental agencies could utilize this system to monitor illegal activities (such as dumping, mining, unpermitted construction) and gauge environmental concerns (drainage issues, problematic runoff, deteriorating infrastructure) to better protect the public. This system could also be used to refine our property tax system and work towards a more equitable means of assessing our properties.

None of these potential changes and upgrades would have been possible 40-50 years ago; the invention and adaptation of GNSS have allowed these technologies to emerge. We continue to find new ways of measuring and mapping, so using these new techniques should be foremost on our minds to make these previous tedious tasks much easier to accomplish.

The hurdles to change

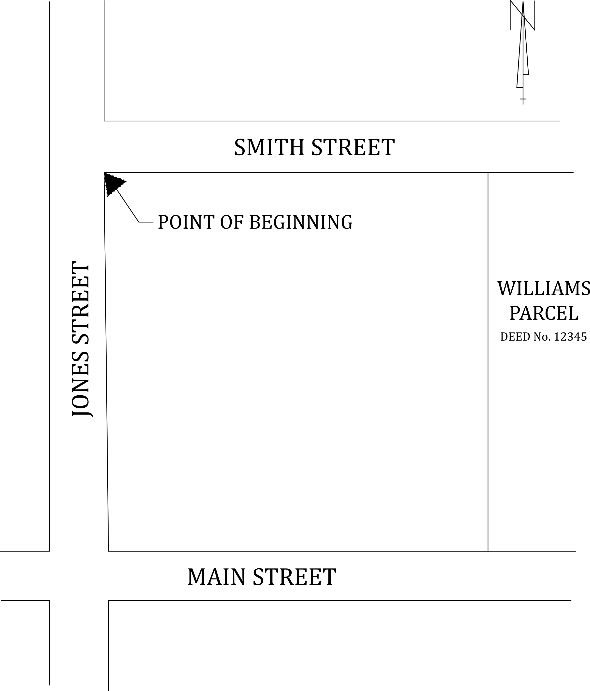

The biggest challenge, in my professional surveying opinion, will be adapting millions of parcels and deeds to a new database and applying them to the current datums. For instance, here is an example of potential (and recordable!) legal description:

“Beginning at the northeast corner of the parcel, said corner being the intersection of the south right-of-way line of Smith Street with the east right-of-way line of Jones Street; thence easterly on the said south line of Smith Street to the northwest corner of the Williams parcel per Deed No. 12345; thence southerly on the west line of said Williams parcel to the north right-of-way line of Main Street; thence westerly on the said north line of Main Street to the intersection with the said east right-of-way line of Jones Street; thence north on the said east right-of-way line of Jones Street to the point of beginning.”

While this is only a made-up example, it does represent a generally accepted legal description for parcel conveyance in most recording agencies. What does a mapping department do with this kind of legal description to place it accurately within a GIS or cadastre? Unless the four adjoining legal entities (Smith Street, Jones Street, Main Street, and the Williams parcel) exist geospatially within the database, the technician will have a tough time inserting this parcel into the records. Unless the entire surveying community is up to the challenge of working solely in an approved geospatial datum for all their work, much of this effort will not accomplish anything.

The other roadblock to converting our current systems to a cadastre is the rest of the parties who work with legal documents, plats, and infrastructure; they may not be up to the challenge for making a radical change for the better. From the assessor’s, recorder’s, and mapping offices to the title companies and attorneys, many have an attitude that the system is too big to revamp. Because they only work in one part of the overall system, they do not see the benefit of blowing it all up to make it a more robust and useful database.

Practically speaking…

Revamping of any system within the varying levels of government is costly, no matter what branch or region is discussed. Governmental agencies are being asked every day to do more with less and provide more value in their services with few numbers of staff.

While there may be a large upside to converting our existing databases to a cadastre, the downside is the effort and cost to do so. Yes, the new system would be scalable and easily adaptable for more infrastructure growth and could be expanded in an infinite number of ways. We can liken this proposed idea to converting all weights and measures to the Metric System: going metric will make lots of tasks and procedures easier, but flies in the face of everything we know as a society.

However, our ongoing battle with COVID-19 has shown we can adapt to radical changes. The cadastre is a better system, but I do not want another worldwide disaster to convince us to change.

Follow Us